Visit any public school across the country and you’re likely to see an emphasis on group interaction, class discussions, and an insistence on participation by all. It sounds inclusive, but is it? It may be that this typical school environment benefits one type of student but puts others at a significant disadvantage.

According to Swiss psychiatrist Carl Jung, generally, people can be divided into two distinct groups, extraverts and introverts, and what separates them comes down to where they derive their energy. “Each person seems to be energized more by either the external world (extraversion) or the internal world (introversion),” he wrote. Jung described extraverts (spelled extroverts in contemporary dictionaries) as people who tend to be outgoing, conversational, and enjoy social interactions. Introverts, on the other hand, are usually quiet, reserved, and introspective, and they need time alone to recharge.

Though these labels are not exclusive or absolute—extroverts still need quiet times and introverts do enjoy some socializing—in general, most people tend to lean more toward one of these two personality types. “So extroverts really crave large amounts of stimulation,” explains Susan Cain, author of Quiet: The Power of Introverts in a World That Can’t Stop Talking, “whereas introverts feel at their most alive and their most switched-on and their most capable when they’re in quieter, more low-key environments.”

But most schools, it seems, are geared more toward extroverts than introverts.

The Typical Classroom Model

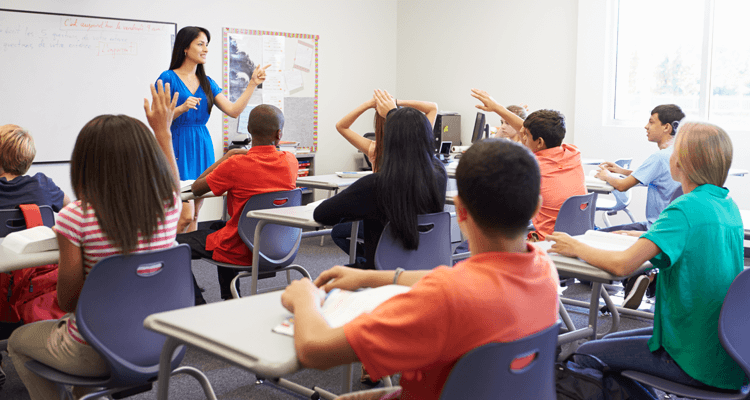

Schools, like many organizations, often put an emphasis on group activities. Children are divided into groups to foster collaborative learning. Teachers encourage class participation and conversation. The rise of project-based learning often utilizes team-building activities.

Extroverts will likely thrive in such environments—enjoying the chance to speak and share their ideas with their teachers and classmates. They are usually eager to raise their hands, and they are often the first to jump into a discussion.

But such class dynamics can be less effective for introverts, who need time to process information and can feel drained in larger groups. These students may choose to observe quietly and may learn the material better when they can read and study it on their own.

The Impact on Grades

Many teachers typically encourage quiet students to speak up, participate more in class, be more assertive, and join in all activities. Sometimes an introverted student’s instinctive reluctance to comply with such requests is reflected negatively in their grades and performance reviews.

In an article for The Atlantic, English teacher Jessica Lahey wrote, “I have experimented with many different grading strategies over the years, but class participation remains a constant in my grade book. It counts for a lot because we spend a large percentage of our of class time in dialogue.” Lahey argues that introverts must learn to speak up and master the skill of interpersonal communication, no matter how much it goes against their natural grain. After she received a number of negative responses to her article, however, Lahey wrote a follow-up post acknowledging that she had more to learn on the subject, although she still maintains her class participation grading policy. “I realized that I needed to come up with new techniques to encourage sharing in the classroom that stemmed from collaboration and joint efforts and offer ways for less verbal students to articulate their knowledge,” she wrote.

Susan Cain believes that, in some cases, teachers may be showing a bias for extroverts when they demand more interaction and verbal participation from their students. “And for the kids who prefer to go off by themselves or just to work alone, those kids are seen as outliers often or, worse, as problem cases,” Cain notes in her popular TedTalk. “And the vast majority of teachers report believing that the ideal student is an extrovert as opposed to an introvert, even though introverts actually get better grades and are more knowledgeable, according to research.”

The Effect on Self-Esteem

When teachers reward outgoing behavior by grading on class participation, they may also be sending an unintended message to their students. If extroversion and group dynamics are held up as the ideal, introverts may begin to see their own personalities as inferior and in need of changing. “I think we need to do widespread education of teachers about what temperament really is,” says Cain, “so that their reaction to introverted children is not, ‘Oh, here’s someone who I need to make more extroverted.’”

Ideally, all students—introverts and extroverts—should be comfortable with their own individual personalities. If kids are fighting against their natural inclinations, it will be harder for them to discover their own potential and succeed at what they do best.

Change May Be Coming

Although Susan Cain predicts that classroom changes to accommodate more introverted students will likely be a slow process, she is encouraged that some schools have been responding positively to her message. For now, she suggests that teachers build quiet time into the class day for students to read or think by themselves. And recess, she suggests, could be expanded to allow students to choose to sit alone or in smaller groups, rather than being forced to join in larger activities. Citing a psychology study by Russell Geen in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, Cain said in an interview with Ideas.Ted.com, “If you take that research and apply it to the classroom, it’s crying out for a solution that is less one-size-fits-all—and that allows students to pick the amount of stimulation that is right for them in that moment.”

Solutions for Introverts

Technology can be one way to even the playing field for introverts. Email, class discussion forums, and apps are all helpful ways to allow introverts to join in the discussion and share their ideas while communicating in a way they are comfortable with. “We don’t want the voices of our more introverted students to be lost or dismissed,” writes English teacher Jordan Catapano in an article for TeachHub.com, “and there are several advantages technology in the classroom offers that helps these introverted students be themselves, but in a more connected way.”

Cain agrees that the use of online technology can be especially helpful for introverted students, “… the fact that a student is participating in a class discussion or a class blog online removes some of their own psychological barriers to participation,” she notes in the Ted.com interview. “The same kid who might not raise their hand in class might write something really interesting into some kind of classroom app or blog.”

In addition to the technology advantages, online schools can be an ideal learning environment for introverted students who prefer an individual education in quieter surroundings. Students in virtual public schools have more flexibility in choosing when and how they interact in class discussions. And in an online environment, they can more easily converse with their teachers with one-to-one opportunities. Visit K12.com to learn more about how online learning works and to request an information kit.

If you’re the parent of an introvert, be sure to reassure your student that there is nothing wrong with the way they prefer to learn and interact with the world around them. Seek out resources, such as Introvert Dreams, a coloring book specifically for introverts, or children’s books that feature introverts positively in the story, to encourage them to be themselves.