I am writing this blog in my studio here in the Taconic Hills of upstate New York. Old Man Winter (perhaps Old Person Winter is more appropriate) has reared his (or her) frigid head. I’ve got my shovels ready, and, like me, the animals around me are going about the business of preparing for the cold. Soon, bears will be showing up on my back porch; they are getting ready to survive more than a few months of snowy, cold conditions.

Winter Hibernation

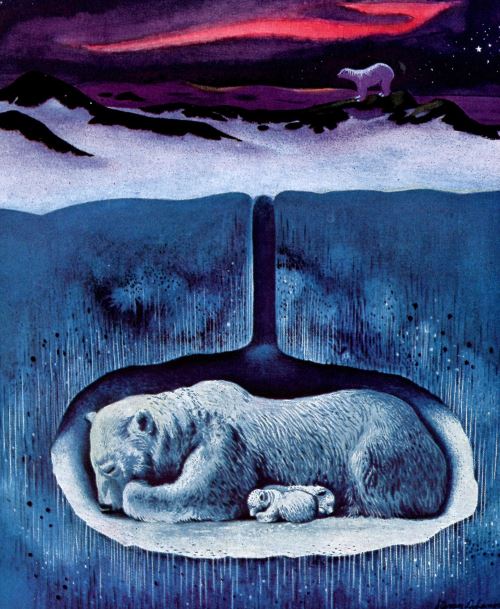

When we think of the survival of winter animals we first might think of hibernation. Most of us know that black bears, grizzly bears, and polar bears hibernate in dens, that is, they undergo a period of reduced (or no) movement, lower body temperature, reduced heart rate, and the slowing down of most other metabolic processes. Bear hibernation is of a lighter sort; animals of the northeast US, such as the eastern gray squirrel, the red squirrel, voles, moles, field mice, and the short-tailed shrew have a deeper form of hibernation; they are curled up in nests with their metabolisms severely depressed until April. Among the deepest of all hibernators are the woodchuck and the eastern chipmunk, Tamias striatus. Most of the bats around here hibernate too. Hibernation is often not continuous. Bears and rodents may move around in search of food, but soon are back in their dens living off of the stored food resources they gathered in the fall.

Image by dok1 via Flicker/ CC 2.0

Winter Adaptation

Not all mammals that live around me hibernate. The bobcat doesn’t, nor does the fisher. Deer don’t either, but in October their coats change dramatically. It is amazing to see the sleek tan September coats of a deer change in one month or less to a deep brown, curly woolen animal. Winter is not easy for a marten or a fisher either, but they don’t check out like a woodchuck.

All animals that live around me have to survive the winter. Insects do it mostly by burrowing deep in the ground and just waiting until it gets warm. Many species of invertebrates cope by their very life cycle—no adults live in winter, only deeply buried eggs that hatch in spring. And consider this animal, the toad.

Image by Cephas / CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons

Toads and frogs are cold-blooded, more accurately they lack the metabolic processes needed to keep their body temperature constant. They are exotherms (from heat out there). They are at winter’s mercy. But their adaptation for winter is a spectacular one. Many frogs, toads, and salamanders bury themselves in mud or in the leaf litter of the forest floor and let their body tissues freeze. Why is it then that they don’t die—no living thing withstands temperatures below freezing, can it? It turns out that they can. Most amphibians that go torpid in winter do two things to ensure their survival; they reduce the amount of water in their cells in fall, and then they make antifreeze—exactly the same chemical (ethylene glycol) that is in car antifreeze. When ice crystals form in a toad’s body they remain very small, not piercing and needle-like but as granular small crystals. The cell walls are not pierce by ice and remain intact all winter long. A toad will actually thaw out in spring.

Winter Migration

Though many birds remain here in the Taconic Hills all winter, most species migrate. One of the great strategies for winter is to just avoid it, by flying a thousand miles south. But hibernation is not unknown in birds. When it comes to a condition that is just this side of pure hibernation, no bird exhibits it better than the poor will of the central US plains.

Image by Laura Gooch via Flickr / CC by 2.0

The poor will has issues with winter for two reasons. First, it is really small so its surface to volume ration is very high—it loses heat easily. It eats a lot in the summer but in the winter it is at a distinct disadvantage, no food and even though it moves south in winter it still finds winter challenging.

I could provide a thousand examples of strategies for winter survival of animals. As I have mentioned in previous blogs, however, science is not about learning isolated facts, but in assembling those facts into more general knowledge. Hibernation, coat change, torpor, antifreeze in the cells, and flying south for the winter are all adaptations—traits that allow individuals to survive and pass along their genes to the next generation.

This winter, when I am shoveling that path from my house to my writing studio, I’ll look into the forest and try to remember that animals have to get through this winter too.

Image Credit – State Farm / CC by 2.0